Choir

One of the other outcomes of learning to play guitar, and having been the chairman and compere of the Folk Club and the public concerts that we gave, was that I became quite well known as an entertainer.

One day a neighbour, Bill Evans, an ex-Royal Marine, living a few doors down the road came to me and asked if I would come and entertain at the annual dinner and dance of the Bridgend Branch of the Burma Star Association to be held in the Conservative Club. I agreed and duly turned up to do a half hour spot. When the Burma Star people had finished eating, and were preparing to be entertained before the dancing started, Bill approached me and said that one of their members wanted to read some poems, so would I mind if he put him on first. I had no objection, and stood around while this white-haired follow read two very funny poems, one of which was called “Whatever Happened To Phipps?” The other was the words of a well-known Irish song about the builder and the barrel of bricks.

I was then introduced and did my 30 or so minutes, came off and went to the bar in the corner of the room for a pint. The white haired chap was standing there, and I asked him if I could have a copy of the Phipps poem because I had enjoyed it so much. He became very exited and said how much he had enjoyed my performance, and would I like to join his choir because they could do with a soloist, especially as they were going on tour next October and I would be welcome. He was Gerwyn Miles, the Chairman of the choir. I was flattered, of course, and was interested in becoming soloist in a choir and widening my horizons, and asked him where they were going on tour. He said it was Canada, which I thought was very exiting. I was still teaching guitar at the Adult Education Classes at that time but they were due to finish in March, so I agreed I would give it a go in March, because I had a class on Tuesday evenings, which was also when the choir practiced.

I met Bill Evans a number of times subsequently, because I was asked to adjudicate in the Talent Competition, which was held every summer in the Grand Pavilion, Porthcawl, and ran for eight to ten heats, and then the Finals. The other adjudicators for the heats were also well-known local entertainers, some professionals, and performers’ agents, but the Finals were always adjudicated by local dignitaries. Bill, having served in the Royal Marines Band, played the Clarinet and Saxophone, and every year he entered the competition, always coming on stage when introduced carrying his clarinet on his shoulder like a rifle, and marching across the stage, doing a smart about-turn, marching back to centre stage, a smart right turn, and a military salute. He was always very good, especially playing “Stranger On The Shore”, which he always played, but he never won. I notified Orwig Owen, the Principal of the Evening Classes that I would not be doing a First Year guitar course the next year, and in February 1982, I joined the Bottom Bass Section of the South Wales Burma Star Choir in The Ponderosa Club in North Cornelly. Everyone was very friendly, and Jack Hopkins made me sit next to him and took me under his wing. He was a retired painter and decorator, cantankerous and very outspoken, but we got on like a house on fire. Our conductor was Cliff Goss, who had taken over when the original conductor, Bill Ellis, gave up. Bill subsequently became the President of the choir. Both were, of course, holders of the Burma Star, having served in the Far East during WWII, when Britain and America were fighting the Japanese – and beat them by dropping two Atomic Bombs on them. The choir was about 40 strong, but not all were Burma Star holders. The choir was formed originally in 1970 by members of the Burma Star Association, who had been going to the Association Re-unions each year at the Royal Albert Hall, and after the formal bits, plus the entertainment, they all retired to the numerous bars set up for various regiments, units, divisions, etc., so that they could meet up with old comrades from the war days. Inevitably, so the story goes, the Welsh contingent would start singing after a pint or two, and the others nagged them to form a proper choir and come and entertain everybody from the stage during the Re-union. A meeting was arranged in Swansea, and the choir was duly formed, with members from as far afield as Llanelly, Swansea, Bridgend and Cardiff, and they practiced in Landore. Gradually, members from the more distant places dropped out and eventually, they moved the practices to the Pondorosa Club in North Cornelly, and welcomed brothers, sons, friends, etc., to join and enlarge the choir. The members were then from Swansea, Morriston, Bridgend, Porthcawl and a few outlying areas, and it was here that I joined them, to help raise money to pay for the forthcoming tour to Canada in the November, and learn all their songs. Shortly after I had joined, the choir moved again, this time to the Welfare Hall at Pyle, which was owned by the local Council, and the choir was not charged rent, and we practiced there for a number of years. Eventually the Council decided to give the Welfare Halls and recreation centres greater autonomy, and Pyle Welfare realised that we were not paying rent, and decided to charge us some extortionate weekly fee, so we moved to the Pyle Royal British Legion Club, where we could practice for nothing, but spent a lot more on cheaper beer in the bar after practices.

Show on a Shoestring

One of the consequences of joining the Choir was that I met Terry Griffiths, another Bottom Bass, who entertained by doing marvellous impersonations of Al Jolson, complete with black face and white gloves. He was also a member of an amateur variety group in Porthcawl, who did shows in the Grand Pavilion each year, usually called Show on a Shoestring or some such name. He persuaded me to come to meet them and told them of some of my performances with the guitar, including a song I used to sing called Whistle, Daughter, Whistle. This was a conversation between a girl and her mother, the girl wanting a man to marry and her mother offering her a sheep or a cow, etc., instead if she whistled. When singing this song, I used two female wigs, one for the daughter and one for the mother, which was chaotic, but usually considered hilarious by the audience. When offered a man, the girl whistles. I was invited to sing it in one of their shows, and subsequently was persuaded to do other items. One year, I did the Lavender Cowboy, a song about a cowboy who wore Chanel No.5, and rode side-saddle, and for this I was kitted our with a farcical cowboy outfit with a huge cowboy hat.

Another year, I was told by the producer that she wanted me to do a music hall number called “Why Do All The Boys Run After Me?” which used to be sung in Music Hall by a man who dressed up as a dowdy woman with hair done in a bun, a straight black dress and big boots. I agreed to do this, but when I went to the outfitters to collect my costume, the one ordered for me was a voluminous pink creation that looked like a huge wedding cake, a blonde wig with long curls hanging down, and high heel shoes. It took me days to get used to walking in those shoes, and then she told me I had to step over the footlights, down a ramp and perform on a platform set up in front of the stage, almost amongst the audience. I never got nervous before going on stage to perform, because in Folk Club concerts I was usually so busy seeing that everyone else was in place in the wings ready to go on, which was a great advantage, not having time to worry too long about performing myself. The company was run by two women, both performers, one very tall and thin and the other short and plump. Then a young man from Port Talbot joined them. There was the inevitable friction and the company packed in. One of the women set up another company, but I went to see one of their shows, and it was all filth, so I never bothered to join them.

Talent Competition Adjudicator

I also, as a consequence of all this, became friendly with Roger Price, who was the man in the council’s Leisure Services Department who arranged all the concerts etc., for the Pavilion. I also knew him from the United Services Club and it was he who invited me to be an Adjudicator for the Annual Talent Competition in the Pavilion. I did this for several years with two other adjudicators, one of whom ran a theatrical agency in Swansea, and supplied artists for theatres all over South Wales. I also became very friendly with the Manager of the Pavilion, with whom I adjudicated the talent competition in a workingmen’s Club in Tonyrefail. He always drove and we usually arrived while the audience was still playing Bingo. On arrival, we were given a pint of beer while we waited. When we went in to take our places for the contest, we were given another pint. The audience were seated around the sides of the dance floor, in the middle of which we, along with their local pianist, who was the third adjudicator, sat in splendid isolation. As our glasses got near to empty, one of the committee members brought along another refill, and so it went on. How he drove back to Porthcawl safely, I shall never know.

I had many happy hours at the Pavilion Talent Competitions, and one year compéred the Senior Citizens’ Talent competition, introducing the competitors and then entertaining the audience while the adjudicators retired and made their decisions. I had also adjudicated at this competition for several years, but was never invited to compére it again!

SWBSC Trips to Canada

The trip to Canada with the Burma Star Choir for which I was conscripted into the choir was a great success. We flew to Toronto, and our first destination was North York, one of its suburbs, where I stayed with a man who had been handed over to Dr. Barnardos at the age of six, by his mother, who was single and could no longer look after him. He did not know where his mother was taking him, or why, but he remembered going to an office where his mother spoke with a man, and eventually left, leaving him there with the man, who took him to a Children’s Home, where he stayed. He did as he was told and did not get into trouble, until he was persuaded by another little lad to run away. He reluctantly agreed eventually, and off they went, but were soon caught and taken back, but he was now branded “a runner”, so he was transferred to a Home on the Isle of Wight, from which presumably it was thought that he could not run away. He was later sent, with thousands of other Barnardo boys, to Canada, where they were looking for young boys to work on farms. He ended up on a farm where he was given only a pair of trousers and boots and a shirt, given only enough food to keep him working, and treated as a skivvey. He told me that on Sundays, he had to go to church, but while the family rode in the horse and trap, he had to run across the fields to get there the same time as they did. Although Barnardos had supplied him with clothes, the farmer gave those to his own son, and Charlie only wore them when the Bardados officer came to see how he was getting on, and had to take them off again as soon as the officer had left. He stuck it for a number of years, and finally ran away with another boy, who wanted to go to USA to start a new life, but Charlie wanted to stay in Canada, so he went North and the other boy went South. He found work on another farm, where he was well treated, but eventually a Barnardos’ officer tracked him down about two weeks before Charlie’s 18th birthday. The officer told him he had other enquiries to make and would be back to fetch him. He came back on Charlie’s birthday, and feigned surprise to find that Charlie was now 18 and free from Barnardos. He eventually married and lived a very happy life, but never lost his cockney accent. I had notified my cousin Edna and her husband of the concert, and as they lived only a short distance from Toronto, they were able to come and hear us, and have a mini re-union, which was great. From Toronto we went to Niagara Falls, where I met an old gent in his eighties, who had tugged on my sleeve after the concert we did there, and asked if there was anyone from Gowerton in the choir. Bearing in mind that the choir was based in Pyle with a catchment area of a few miles, it is amazing that he picked on me, who was born in Gowerton. He asked about a number of people whom I knew and I was able to bring him up-to-date.

His family had emigrated to Canada when he was about 12 years old, and he had lived in the large house in the middle of Gowerton, now occupied by the Piper family, to whom his father had sold it before emigrating. When we returned home I went to Gowerton and took photographs of the house and other parts of the village and sent him them, and we communicated until the choir went back to Niagara Falls two years later, when he showed me the Bible he had been given by Bethania Baptist Chapel in Gowerton, signed by all the deacons and the minister when he left for Canada. He also produced a huge pile of photographs from when he was a small boy in the village, and expected me to recognise all his old friends. We continued to correspond for a few years further, and then I heard nothing more from him. Presumably, he had passed away. After all, he was well into his eighties when I first met him. I stayed with a delightful family in Niagara Falls who took me around to see all the sights, and with whom Diana and I stayed when we went out with the choir again in 1984. From there, we went to Syracuse in America, where I met up with Peggy Thomas, who was the same age as Marion. She had married an America soldier during, or just after World War II, and moved to America with him. When we arrived at the hall where we were to do the concert, we found the place locked up because the caretaker had forgotten about the concert, so a large crowd collected on the pavement, and along came this woman shouting, “Where is Ifor Davies?” and then wrapped me in her arms and told me that her mother, known to everyone as Auntie Mag, and who was still living opposite my mother in Mount Pleasant had written to tell her that I was coming with the choir. She proceeded to tell the assembled crowd how, when I was born, she was with Marion, then aged 8yrs, in our house, when the midwife came down stairs with me in her arms to show me to Marion, but being afraid that Marion would be too exited and would drop me, she gave me to Peggy to hold, minutes after I was born, so she was the first person to hold me after the midwife. The caretaker eventually arrived and finally we did the concert there, and then moved on through the Adirondack Mountains, stopping at Lake Placid for lunch. There I ate the largest sandwich we had ever seen, about 4 inches high, so I had to start at a corner and nibble my way into it. I also found a tobacconist shop from which I came away with a plastic carrier bag full of tobacco and cigars of various sizes, for which I had paid the equivalent of about £5. We carried on from there to return into Canada at Montreal, where I became very friendly with the chairman of the Montreal Welsh Male Voice Choir in the Welsh Chapel, but I lodged with Leslie West and her husband, David, with whom I kept in touch for several years, but who stayed with Norman John when they visited Wales with their Choir. Leslie was a very attractive, lovely lady, studying English Literature at the university, while her husband was a drunken, rude, uncouth man, half Indian, and who worked in a glass bottle factory. He took me to a local Indian reservation and introduced me to some of his Indian friends there, who lived in very smart houses and drank very heavily, and he also gave me two glass bottles made at his factory as a parting gift when we left.

Leslie heard me reciting “Timothy”, the poem written by Jan Smith of Maesteg. Leslie decided the way I recited it, it sounded like Dylan Thomas’ work, and she was doing a dissertation on Dylan at University, so she got me to recite Timothy in the Dylan Thomas style, and she would take it and try to kid her class it was a newly discovered work by him, and, what is more, recorded by him. To get the sound right, I had to stand in the kitchen and she stood with the tape recorder in the living room. When we left, she presented me with a new lavatory brush on which she had drawn what was supposed to be my face. As I did not have room in my suitcase, and we had to go to Ottawa before returning home, she agreed to keep it for me until the choir came again.

On our next choir visit to Canada, Diana came with us and we stayed with them again, and she still had the lavatory brush, but again, I left it there. By the time the Montreal choir came to Wales a few years later, she had left and divorced her husband and was now shacked up with a coloured man who sang in the choir and treated her properly The conductor of the Montreal Welsh Male Voice Choir was Twm Edmunds, from Pontardawe who had arranged a Canadian folk song, which we had learned in order to sing it while in Canada, “Farewell to Nova Scotia”. He stayed with us in Bridgend several years later when his choir came to Bridgend. He had only two ambitions in life, one being to sing in the Royal Albert Hall, London, and to be buried in Pontardawe. Sadly, when they left Bridgend for London, he was very unwell, but did stand to sing with the choir in the Albert Hall, but after two songs had to remain seated. After the concert he was taken directly to his sisters’ home in Pontardawe, where he died two weeks later, and was buried there, thus achieving both his ambitions. From Montreal we went to Ottawa, to another Welsh community, and then back to Toronto for the flight home. Everywhere we had stayed, the people thought we were tremendous, just, I suppose, because we were Welsh and they were all Welsh Ex-patriots, but they all said we had to come back again, and we told everyone we would be back in about two years

We talked so much about this incredible experience, for about six months, when I reminded the committee we had promised to return in two years, and that was only eighteen months away. As we would have to raise a lot of money to make it possible, we had better start work now, if not sooner. Everyone immediately buckled down to fund raising again. One event we organised was one of the first Car Boot Sales in the area. Bill Goss announced that he was getting too old and he would not be able to manage another trip to Canada, so he resigned as Musical Director in favour of David Davies, who played brass wind instruments, knew his music, and was our Deputy Conductor

When, in 1984, we went back to Canada the second time, we met up with our friends in Niagara Falls, Montreal, and Ottawa, but also visited a town near Lake Huron and drove through part of the huge Algonquin National Park, through which there is only one road, but covers most of Quebec. We saw a beaver dam in a river alongside the road. I had told Diana about the incredible autumn colours in Canada, which I had seen on the first trip, and she was looking forward to seeing them for herself. Unfortunately, there had been a short icy-cold snap about a fortnight before we arrived and, apart from a quick run from Niagara Falls to Lake Eyrie with the family we were staying with, where we did see some lovely colours on the trees, the rest of Canada had no leaves at all. All the way through Algonquin National Park, the trees were completely bare. The first really magnificent autumn colours we saw on trees on this trip were on the M4, on the way from Heathrow back to Bridgend. The Montreal Choir came to Wales for two tours subsequently and our Choir made all the arrangements, and hosted them while in Bridgend. We, however, never went back to tour in Canada.

After our second visit to Canada, the Chairman, Gerwyn Miles, suddenly resigned as Chairman, and as he had insisted on electing me Vice Chairman before our second visit to Canada, I had to take over as Chairman until the next AGM. The Secretary of the choir was Joe Fisher, who was not the easiest of men to get on with, and friction had developed between them, because they could never agree on anything. The situation became more difficult until they would no longer speak to each other, and Gerwyn told me he was considering resigning as Chairman. I tried to persuade him not to do so, because I spoke to both of them and knew that Joe was also planning to not stand for Secretary at the AGM if Gerwyn was re-elected as Chairman. During this trip to Canada, there were several decisions that could not be made until we arrived at a destination and knew the local situation. Because of the rift between the chairman and the secretary, I, as vice-chairman, when a decision had to be made about anything, had to go and ask Gerwyn for his views up the front of the coach, and then go and speak to Joe sitting at the back of the coach and then consult with the Treasurer in the middle of the coach, establish a decision and then announce to the choir what we were going to do. Gerwyn finally told me that he had made up his mind to resign, and I advised him that as we always elected the Chairman first at the AGM, then the Vice Chairman, the Secretary and Treasurer, in that order, and that I knew that as soon as he was re-elected as Chairman, Joe would refuse to stand as Secretary, and the problem was solved. After all, Gerwyn was a founder member of the choir, had been elected as its second chairman after the first chairman left the choir, and had virtually run the choir ever since. Within two weeks of returning home, Gerwyn gave me his letter of resignation, and I had to take over as Chairman. At the next AGM, in May 1985 I was elected Chairman and remained so until I also resigned in a huff, in 1999.

Lorient Festival

One of the first exiting things to happen when I became chairman of the Choir was that one of our members from Port Talbot told us about a huge Celtic Festival in Lorient , Brittany, and he knew someone from Port Talbot who was on the committee, so we might be able to go there. We contacted this man, who said Lorient was looking for a choir of about 200, so we, at 45 strong, were too small, but he would enquire. He then told us that he had offered the trip to Côr Meibion De Cymru, the South Wales Male Choir who numbered about 500. Weeks later he told us that De Cymru could not agree on which 200 would go, because they all wanted to go. Eventually he came back to us and said he was fed up waiting for De Cymru to decide and we could go.

So, in 1986, we failed to get 200, but by contacting choirs in an ever-widening area until we got as far as Cardiff and Swansea, we assembled a choir of 120 singers to go to the Lorient Celtic Folk Festival, where we excelled ourselves, and established strong ties with Kanerian an Oriant, (the Lorient Singers,) a large mixed choir conducted by Jean-Marie Airault, a bank official in Lorient, who became a close personal friend, and with whom we have kept in close touch ever since, arranging tours in Wales for him and doing tours arranged by him for us in Brittany. When we arrived in Lorient, we were met by Jean-Marie, who asked how we had got on learning “Ymadawiad Artur”. We asked what that was and were told it was the song we were supposed to be singing together in a big concert the next Saturday. The chap who had invited us to come had told us there was a song that had been suggested we sing, but it was long and not very cheerful, and he did not think it was worth learning, so he didn’t give it to us. The result was that most of our time that week was spent in rehearsal with Jean-Marie’s concert learning this and another little Breton folk song.

Although we had a marvellous time at the Festival, especially in the evenings sitting outside a particular café in the town centre, we in fact saw very little of the rest of the festival. We had to do concerts in various places, and one memorable one was in Nantes Cathedral, where David Davies, then our conductor, insisted that I read the Twenty-third Psalm while the choir hummed the tune Crimond, which made the hairs of one’s head stand up. The acoustics in the cathedral were tremendous, but it may be that because the sound echoed and re-echoed around all the huge pillars, our singing might have ended up as just a jumble of noise for the audience. They all enjoyed and complimented us, anyway. We spent most evenings when free at our little café, where a glass of beer was 7fr at the early part of the evening and increased in price as time wore on, and by midnight was about 14fr, but for us, because we were singing and drawing in the crowds, it remained at 7fr. We later discovered that the concert in Nantes was not at the request of the Festival Committee, but it had been arranged by the man from Port Talbot who had led us to believe he was on the Festival Committee, and so there was an almighty row, in which we, fortunately, were not involved. We did become involved, however, when this man went to the Festival Committee towards the end of the week, asking for money to pay hotel bills for the numerous hangers on whom he had invited, especially from Côr Meibion De Cymru, including its Chairman, President, a soloist, a doctor and many others, plus their wives, all of whom had nothing to do with our choir. He had charged us £40 each to go, £90 for wives and £120 for others who wanted to come. Although the choir was only 120 strong, we had four large coaches to take us there. When the Committee objected, he blamed it all on Ogwyn Lewis and myself, who had done most of the actual organisation as far as the choir was concerned but not the booking of accommodation, travelling, etc. The Festival Committee asked us both to meet them, and Ogwyn was able to produce his immaculate records of what everyone had paid and how much we had given this man. They asked us to come to a Committee meeting and tell the whole committee in his presence, which we agreed to do, but he refused to attend if we were to be there. It was arranged for us to be in the room well in advance of the meeting, and he thought we would not be there. When he arrived and saw us there, he turned and walked out, and the Committee was left to meet all the bills. We learned later that no Welsh choirs were to be invited to attend the Festival in future, and this, in fact, was so for several years, and the man involved has been banned for life.

One of the consequences of visiting the Lorient Festival was remarkable. We were in the huge parade, which officially opens the Festival on the first Sunday morning, when all the participants parade through the town and past the Palais de Congres opposite the harbour. The parade took two hours to pass any particular point and the pavements were packed with sightseers. Every hundred yards or so we would have to sing, in competition with all the Breton pipe bands which were also scattered throughout the parade, and even a 120 strong choir had no chance against the piercing sound of bombards and pipes. The rest of the time we were either singing in concerts in Lorient or in surrounding towns. On the last Saturday of the Festival, we were assembled on the grass bank surrounding a small amphitheatre at the Yacht Club together with Kanarian an Oriant, and watched other groups, dancers, musicians and singers being televised and eventually we did our bit. Most of the time we were sitting in the sun in our places while the TV programme, going out live that night, was broadcasting interviews, views of Lorient, and all sorts of other things for this three hour broadcast. We did later receive a copy of it from Jean-Marie Airault, whose wife had recorded it from the television. Unfortunately, French television uses a different system from ours, so the copies of our recording came out in black and white, although we did watch the original colour copy. Because we had seen so little of the Festival itself, I decided to go again the next year, simply to watch the Festival and take no part, but more of that later on. Amongst the extra choristers whom we had recruited for this trip were several choristers from the Fairwater Conservative Male Choir, as well as from other Cardiff choirs. Among those from the Fairwater choir was one Alex Mullins, a Cardiff magistrate, and treasurer of the St. David’s Hospital in Cardiff, 6’8” tall. big built, and a widower, living alone. He had a remarkable voice and when he joined our big choir he asked me where I wanted him to sing, Top Tenor or Bottom Bass, because his range was such that he could sing all four voices. He settled for Bottom Bass, which was where I sang, and we became close friends. When the Lorient event was all over and dusted, he continued to come to sing with us along with a few of his friends from Cardiff, presumably because we did such exiting concerts in places other choirs could not get to, like singing in the Burma Star Association Annual Conferences in the Royal Albert Hall. Most of them eventually gave up travelling to Pyle every week, and dropped out, but Alex remained a faithful devoted member of the choir until the choir eventually folded. We became great friends, and, not being able to drive, he travelled to Bridgend by bus or train every Tuesday night, and I would pick him up and take him to practice, getting him back to Bridgend station again in time for the last train to Cardiff at 11.05.pm. Wherever the choir went, Alex was always there, and when I fell in love with Brittany and went over there exploring and meeting up with Breton friends, Alex always came too, unless I was going with Diana on a family holiday. He was, and still is, a great, generous and loyal friend.

Alex and I went again to the Lorient Festival with the Penarth Male Voice Choir in 1993. They were only a small choir although it was nearly 100 years old, and although they thought they were the world’s best, they were not very good singers, and very undisciplined. On one occasion, we had to go to sing in La Roche Bernard, some miles South of orient. The Chairman of the Choir and his wife said they would join us there instead of coming on the coach. When we arrived at our destination we learned we had to march in a parade around the town to open their little festival. On the way through the town we passed the chairman and his wife in holiday garb sitting outside a café and later sunbathing on the beach!

Sir Bernard as Pres

The South Wales Burma Star Choir went on from strength to strength, and because we were a choir whose roots were in the Burma Star Association, we had close contact with the Association, and were frequently, every three or four years, invited to sing at their Annual Reunion at the Royal Albert Hall. When Bill Ellis passed away, the Chairman of the Burma Star Association, Air Vice Marshal Sir Bernard Chacksfield, KBE, CB, C.Eng, FRAES, RAF(Rtd), accepted our invitation to be our new President. No one realised how seriously he would take the position. In fact, he attended almost all our Annual Concerts in the Grand Pavilion, Porthcawl, and stayed in the Seabank Hotel for the night. He always brought his wife, Betty, who turned out to be from Gorseinon, and had attended Gowerton County Grammar School for Girls at the same time that I was in the boys’ Grammar School.

Sir Bernard, as President, made sure that the choir sang at his Annual Reunion as frequently as he could arrange it, and was very proud of “his choir”, although we never received any payment from him or the Association, for all the concerts we gave to raise money for them. The Secretary of the Association was from Aberystwyth, an ex-Sergeant in the Royal Engineers, and he frequently called on our services for regional functions of the Association, in Aberystwyth, Bristol, Cheltenham and all sorts of odd places, and also to raise money for the Retired Gurkhas Association. Sir Bernard would ring me up and ask if and when the Annual Concert was to be held, and ask me to book a room in “that little pub up the road”, meaning the Seabank Hotel, Porthcawl. Every year I would instruct the hotel not to give him the bill, and that the choir would pay it, but every year, when I went for the bill, Sir Bernard had already paid it.

Meeting H.M. The Queen

He also was instrumental in getting me, as Chairman of the choir, to be invited to the Royal Retiring Room in the Albert Hall at the end of the concerts, despite my protests that this invitation should be to the Musical Director. In this way I met, and chatted to the Duke of Edinburgh one year. It was the year that we sang “The Burma Star Soldier” for the first time, the last line of which was “Here in the old Burma Star” and I asked him and Sir Bernard what they thought of it. Prince Philip said he thought we were singing about a pub.

Another year I met and spoke to HM The Queen, and wished her a Happy Birthday on behalf of the boys in the choir.

Introduced to H.M. the Queen, Royal Albert Hall, 1995

She smiled and asked me to thank them for her. I also spent time in the Green Room with people like Vera Lynn who sang at the Reunion most years as “The Forces’ Sweetheart” and who visited the Far East during the war to entertain the troops, and they all worshipped her. There was also a tenor who sang in all these Reunions with whom I became friendly. He turned out to be from Waunarlwydd. He would stand by the entrance to the stage waiting his turn to go on with another man standing with him. When his music started, he would stride out onto the stage and acknowledge the huge applause from all parts of the hall, turn to the choir and wave, and at the end of his turn he would turn, waving and stride off the stage where he was met by the other man. It was several years before I learned that he was totally blind

Other Great Times with SWBSC

John joined the choir and I was proud to have him in the bottom bass with me, especially as he had such a good bass voice. He came with us to the Albert Hall and was in what I consider to be the best photograph of the choir we ever had taken. It was taken inside Coety Castle, with us sitting and standing on the stumps of walls inside the castle, and the photographer standing high up on the outer wall.

'sErtogenbosch & Arnhem

The choir also formed an association with a choir in s’Hertogenbosch, Holland, because the town was liberated from German occupation by the 53rd Welsh Division in 1944, and every year invites a Welsh choir to come to take part in their Remembrance Service and concerts. We went several times and saw quite a bit of Holland in the process, and have entertained their choir in Porthcawl and Bridgend several times. On one of these visits to s’Hertogenbosch, of course we had to go to the Memorial of the Liberation of the town, and our conductor at the time decided that we would sing a rather complicated arrangement of Ar Hyd Y Nos, despite our protests that there was no piano at the Memorial and we would have to sing it unaccompanied. He, however, insisted that that was what we were going to sing. He gave a toot on his tuner, and we all started in different keys, and made such a hideous mess of that beautiful song, which was probably why we never went there again.

One year, we decided it would be a good idea to go on the Arnhem Pilgrimage, the annual event for survivors of the attack on Arnhem Bridge by Allied paratroopers, and after quite some difficulty I managed to get an invitation. We watched the Silent March, when all the veterans marched silently through the town to the bridge and back again, all without a command being given or a word spoken, except for the memorial service on the bridge for those who fell in the battle. A young Boy Scout marched about twenty yards ahead of the parade carrying a placard with the words “Silence Please” in large letters. The pavements were crowded with people and not a sound was to be heard, not even the sound of the marching men. It was very moving. We also attended the Memorial Service in the huge cemetery in Arnhem on the Saturday morning. Hundred and thousands of little white memorial stones, some bearing names, and some simply marked “Unknown”, stood in long straight rows around a large open space in the centre of the cemetery. This space was now filled with chairs, for the hundreds of relatives, survivors, and friends who attended the service. The Chaplain of the Airborne Forces conducted the service, and an address was given by the local priest, who then spoke to the schoolchildren who had marched in carrying little bunches of flowers and taken their places, one to each grave in the cemetery. The local priest told them that when he gave the order, they were to turn around and face the headstone at which they stood and as they laid the flowers they were to look at and remember the name on the stone. If there was no name they were to invent one for the person buried there, and remember that name for the rest of their lives. They were then told to turn and lay the flowers. It was a most astonishing and moving moment, and I was quite overcome, and still am every time I relate the story to others. On the way out of the cemetery after the service, there was a man standing silently and alone outside the gates holding up a placard saying, “Veterans, We Thank You.” We also watched a large scale parachute drop, and went to the old church at Oosterbeek, where the survivors held out against the Germans, and those who could escaped in torrential rain through the woods and across the river in rubber boats, which had been brought up for them, while the injured who could not get away held off the German troops. In this church, which still bore the bullet holes and marks where shells had hit it, we performed a concert, which was well attended, although it was only a tiny church, and in this way, we paid tribute to the brave forces who were sent to take “The Bridge Too Far.”

1944-1994 Celebrations

We were also invited by Porthcawl Town Council to take part in a celebration of the 40th anniversary of 1944. This puzzled me at first, because it seemed a strange thing to celebrate. It turned out that Porthcawl was crowded with troops, especially Americans, but also Dutch and Polish, who were here preparing for the Invasion of Normandy, which was to end World War II. Ogwyn and I attended a committee meeting of councillors, along with the Chairman and Secretary of the Porthcawl Male Voice, and we all agreed to do a joint concert at the end of this special week. During the week there were to be parades, and various other events, and displays, and all of Porthcawl put brown sticky tapes on their windows, as in wartime, sandbags were filled and set up around doorways, and so on, and the whole town made to look as it was thought it looked in 1944. Porthcawl Choir and we agreed to do a joint concert, Porthcawl doing the first half and Burma Star doing the second half. Then it was suggested that the concert ought to end with the whole audience joining in a sing-song, singing war time songs. I suggested that if they were to do that, they would need someone to lead the singing, because the audience would not do it spontaneously and would need someone to get them going. The chairman asked if I knew anyone who could do it, and I thought of Gareth Daniels, the colleague of mine from Merthyr who was getting well known as a comedian and after-dinner speaker, but I said I would think about it and come up with some suggestions. While I was making enquiries later, I had a phone call from the chairman of the committee to say they had decided who was to lead the singing – ME. I protested, but they insisted. So it was that I and a well-known pianist in Porthcawl got together and chose a number of songs for the audience to sing. I suggested that, to take us back from 1994 to 1944 we needed a special song to set the atmosphere, and I thought of the Dad’s Army Signature tune, “Who Do You Think You Are Kidding, Mr. Hitler?” Although written specially for the TV programme, Dad’s Army, and recorded by Bud Flanagan, who died about two weeks after recording it, it would take us right back to the days of the Home Guard and the Wartime Britain. The pianist had not heard the song and did not know it, but I sang it to him in his home and he promptly played it and it sounded right.

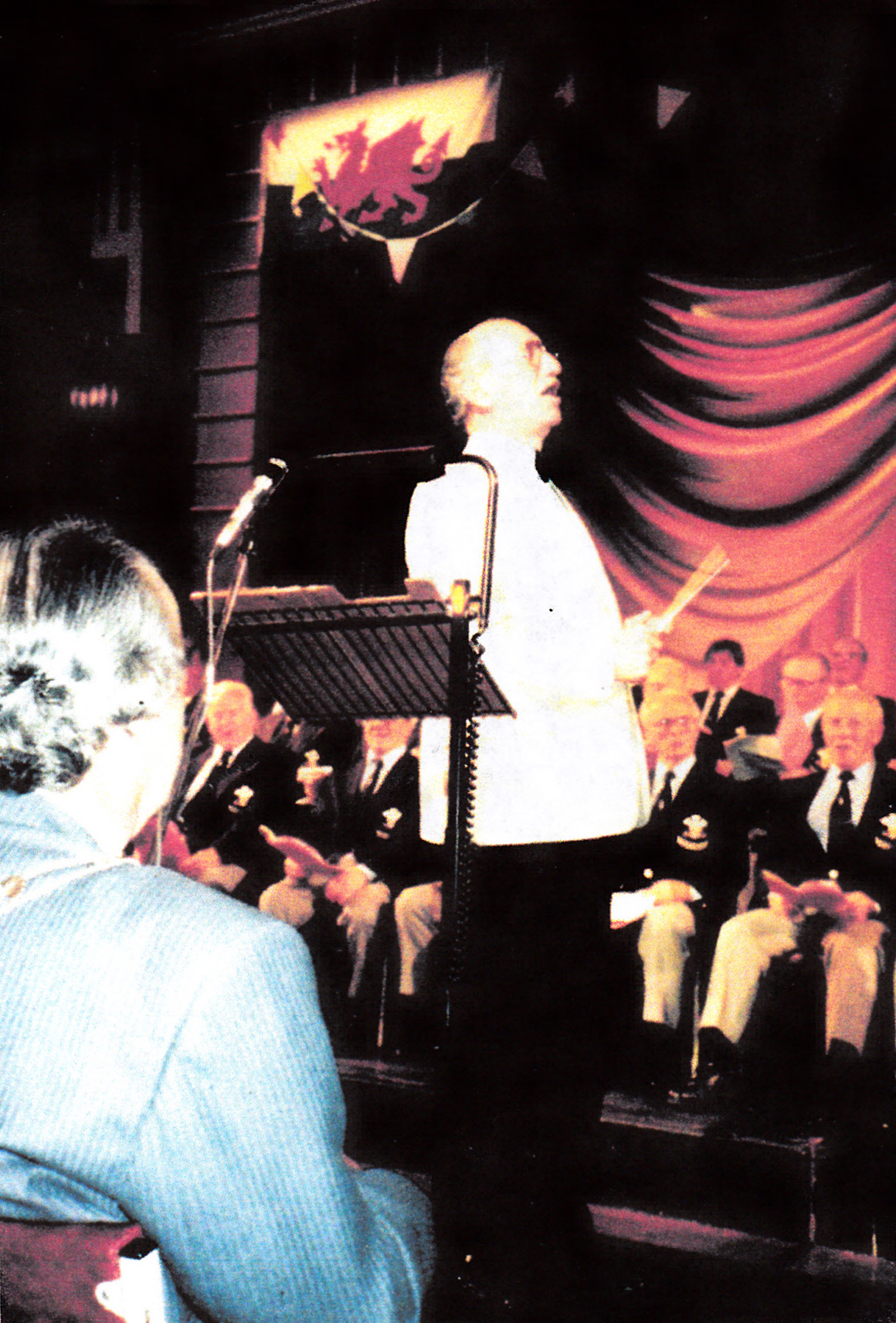

A few days later, I was passing a charity shop in Bridgend and went in to see what they had and saw a white tuxedo on a rack. I tried it on, and it seemed to fit, and they only wanted £2 for it, so I bought it especially to wear for this concert. As soon as the Burma Star choir had finished singing, I dashed off stage, while the compére was thanking everybody and explaining what was to happen next, and I changed into black trousers and this jacket and a bow tie, and a huge conductor’s baton made out of a thick rod painted white that I though would raise a laugh, which it did. It was some months later, when Alex Mullins asked me to compère an Annual concert of the Fairwater Male Choir, and I wore that white jacket again that I realised that it was miles too big for me. It raised a laugh in Porthcawl, but in Fairwater it was embarrassing! So my first attempt of conducting in public was on the stage of the Grand Pavilion, Porthcawl, with a packed audience, two male voice choirs, and no rehearsals.

Conducting a packed audience in the Pavilion Porthcawl 1994. The first time I conducted in public!

It was a huge success, and the committee decided that this event was to be repeated the following year, and this community singing was to be part of it. We did it for, I think, about three years, and then, with changes in the Council and so on, the whole week was abandoned.

The choir has sung in so many places and for so many charities and causes, and with so many other choirs from all over the UK and from abroad. I had a great time with the choir, and have very many happy memories, and also became rather well known in my capacity as chairman, compére and general entertainer.

In about 1993 or 1994, we had appointed a young girl as our Musical Director, who claimed to have a music degree, specialising in conducting. She was the worst conductor we had ever had, and the performance of the choir went steadily downhill, until we had to sack her, but not before she had arranged for us to go to her home town of Goudhurst, Kent, where her father was a hop farmer, and we were all accommodated by the villagers. Our singing was far from First Class, but the villagers, probably because our conductor’s father was the largest employer in the area, thought we were absolutely fabulous.

Festival of Remembrance

In 1994, I received a phone call from Bob Reader, son of Ralph Reader of Gang Show Fame to ask if I could bring the Burma Star Choir to sing at the National Festival of Remembrance in the Royal Albert Hall in the November, because it was to have a Burma flavour. For this we had to be on top form to sing on BBC Television in a concert that virtually everyone in the country watched the night before the Remembrance Service at the Cenotaph in Whitehall. Singing at the Festival of Remembrance concert was a very moving occasion, especially when we stood in the Hall when all the poppies were falling over us. Then, Sir Bernard rang me to say he wanted us in the Burma Reunion because it would be the Fiftieth Reunion, and he wanted “his choir” to be in it. Because of this, I knew we had to get rid of our conductor and find someone to get us back up to scratch in time for these important functions, realising, of course, that during the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, and especially the war in the Far East, we were going to be busy singing for various branches of the Burma Star Association and regimental associations and so on. The only conductor I knew of and who might be available, was Ron Howells, who had conducted the choir some 15 years earlier, but had been sacked at the instigation of Gerwyn Miles after a dispute between them over an issue that had nothing whatsoever to do with the choir.

Ron agreed to come temporarily until we could find someone more permanent. We, therefore, disposed of the services of our young girl, and Ron took over. Our singing immediately improved and we sang magnificently at the Royal Albert Hall, and at remembrance services around this area for the anniversary of VJ Day, and then at the Special Burma Reunion also in Royal Albert Hall. With Sir Bernard as President our visits to sing at the Burma Reunions increased, and I therefore, at Sir Bernard’s instigation, I went to the Royal Retiring Room several times and was introduced to Prince Philip on one occasion and to H.M. The Queen on another. However, as soon as word got around that Ron was back, Gerwyn, suddenly started coming to choir practices again and began a campaign to discredit Ron. Gerwyn had now retired from his work as an architect with the local council, and had virtually left the choir. He had learned to speak Welsh, and then started making a lot of money teaching other people to speak it in classes all over the area. He poisoned the minds of several choristers, and made life so unbearable for him, that Ron, who had stood his ground and brought the choir up to standard for our commitments that year, handed me his resignation immediately after our last VJ concert. I was so angry, not only that Gerwyn had manipulated this situation, but he had persuaded other prominent members of the choir to join his campaign, that I, too, resigned and walked out of the choir myself. The Vice-Chairman, Viv Morris, had to take over until the next AGM a few months later.

Ogwyn, who had surprised me by joining in Gerwyn’s campaign, continued with the choir, but his wife, Mona, had a very severe stroke on our way to a concert in Port Talbot, and although he tried to nurse her at home, eventually she had to go into a nursing home in Neath, near their son. Ogwyn visited her every day, travelling from Porthcawl, but being unwell himself, soon found this too much and applied for admission to the same nursing home. He was accepted but was not allowed to share a bedroom with Mona, so they only saw each other in the day. Mona was unable to speak, except a few words, and although she could use a spoon sometimes, she usually had to be fed by hand. The choir went down there one night to sing to the residents and I went with them. It was the last time I heard Ogwyn singing “In The Garden” as a duet with Ryland Jones. It had always been their party piece in choir Afterglows and such. Then Ogwyn suddenly died 2007, and Mona, gave up the will to live and also died in March 2008. Gerwyn also died in, I think, 2007. The choir’s last tour was to Blackpool to sing at an Annual Conference of the B.S.Association, in the Tower Ballroom. Alex and Russ and I shared a room in a crummy hotel and I spent all my time looking after them.